THE ROLE OF POPULAR MEDIA IN DEHUMANIZING PEOPLE IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

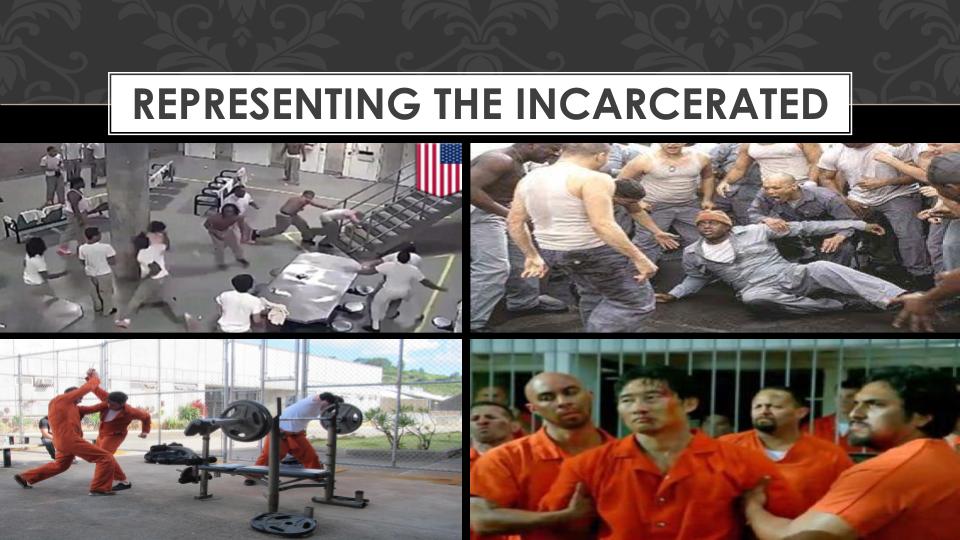

Widespread pejorative labels and depictions of individuals impacted by the criminal justice system—in real-life and the media—dehumanize incarcerated populations. This dehumanization contributes to punitive attitudes, abusive penal policies, physical and sexual abuse of prisoners, general desensitization to such abuse and reluctance to societal reintegration of formerly incarcerated individuals. The role of popular media in dehumanizing people in the criminal justice system undeniably influences the general public’s pervasive negative perception of those incarcerated. This negative misperception of prisoners actually encourages the public’s willingness to legitimize or ignore prison injustices and to countenance the dehumanization of people in prison. According to the A.C. Nielsen Co., the average American watches more than 4 hours of TV each day. According to the Television in American Society Reference Library, watching television influences viewers' attitudes about people from other social, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds. Watching TV also influences the way people think about important social issues such as race, gender, and class. Not only does television, movies and other shared media actively shape attitudes, but they also condition people to respond to things in a collective way, to develop shared feelings of ill-will and hatred, and to react impetuously without further thought or self-examination. Forms of media such as TV and film actively (p)redefine and engineer negative subconscious beliefs about people who go to jail or prison. These beliefs then feed into emotional responses, allowing information to bypass any conscious thought.

The importance of public attitudes towards people in the criminal justice system cannot be denied. In modern democracies, the legitimacy of the criminal justice system depends on the willing participation of members of the public (Viki & Bohner, 2008). The public’s willingness to support the criminal justice system depends strongly on their attitudes towards the criminal justice process (Viki, Culmer, Eller, & Abrams, 2006; Wood & Viki, 2004). As is well known, the USA has increasingly become more punitive and exclusionary over the last thirty years. According to some scholars (Yeomans, 2010), this recent focus on punitiveness and social exclusion has resulted from the interconnections between the media, public opinion and legislative changes. One important aspect of understanding such interconnections is the tendency to dehumanize (Haslam, 2006) people who get involved in criminal justice and in the prison system.

Dehumanizing language and misrepresentative imagery are often used to address and describe people in prison and those formerly incarcerated. The spectacularization of criminal trials, together with false depictions of institutional life in and by the media has provided a misleading and individualistic image of people touched by the criminal justice system, by depicting them as “bad” individuals who willingly break the law and harm others for the sake of their own interest or pleasure. Such misrepresentative imagery has fueled subconscious negative beliefs about people who go to jail or prison within public opinion.

Dehumanizing language and misrepresentative imagery are often used to address and describe people in prison and those formerly incarcerated. The spectacularization of criminal trials, together with false depictions of institutional life in and by the media has provided a misleading and individualistic image of people touched by the criminal justice system, by depicting them as “bad” individuals who willingly break the law and harm others for the sake of their own interest or pleasure. Such misrepresentative imagery has fueled subconscious negative beliefs about people who go to jail or prison within public opinion.

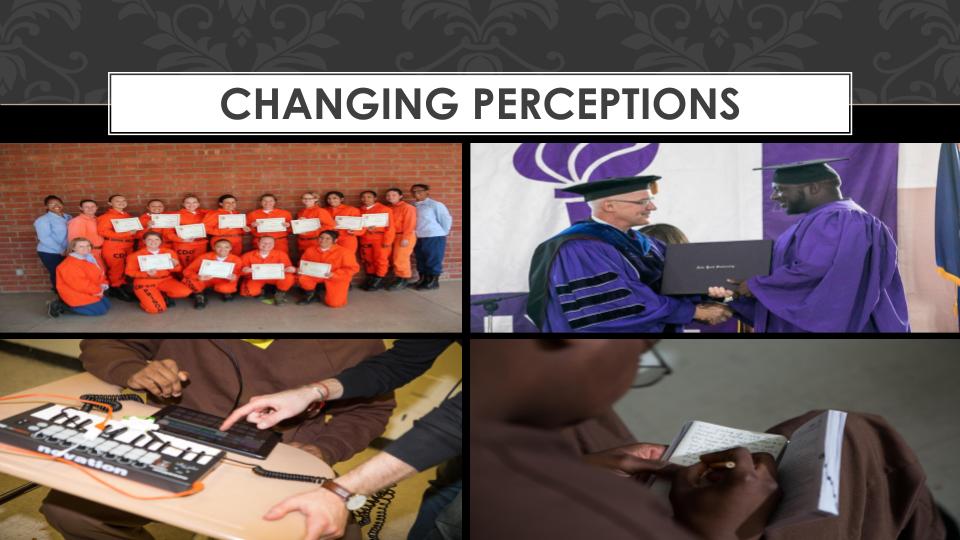

Altogether, the dehumanization and, derivatively, the mistreatment of people in prison largely impedes their rehabilitation, and is not conducive to their successful re entry back into society. If criminality is viewed in essentialistic ways and people in prison are regarded as irredeemable criminals and unworthy of acceptance (Dreisinger, 2016), then public attitudes are likely to be negative about their actual social rehabilitation and reintegration (Kury & Ferdinand, 1999). Examples from Northern Europe endorsing restorative approaches to crime have shown significant success. Despite the above research, existing information and efforts made by activists and organizations lobbying against these conditions, the inhumane treatment continues to occur (Blackler, 2015). This suggests that a larger constituency remains compliant with, and/or ignorant to, these abuses. Thus, targeting popular methods of dehumanization through participatory action research could potentially reduce dehumanization and its detrimental consequences on those who are or have been affected by the criminal legal system.