|

OP-ED BY PASTOR ISAAC SCOTT IN COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR BY ISAAC SCOTT • APRIL 6, 2021 AT 2:11 AM

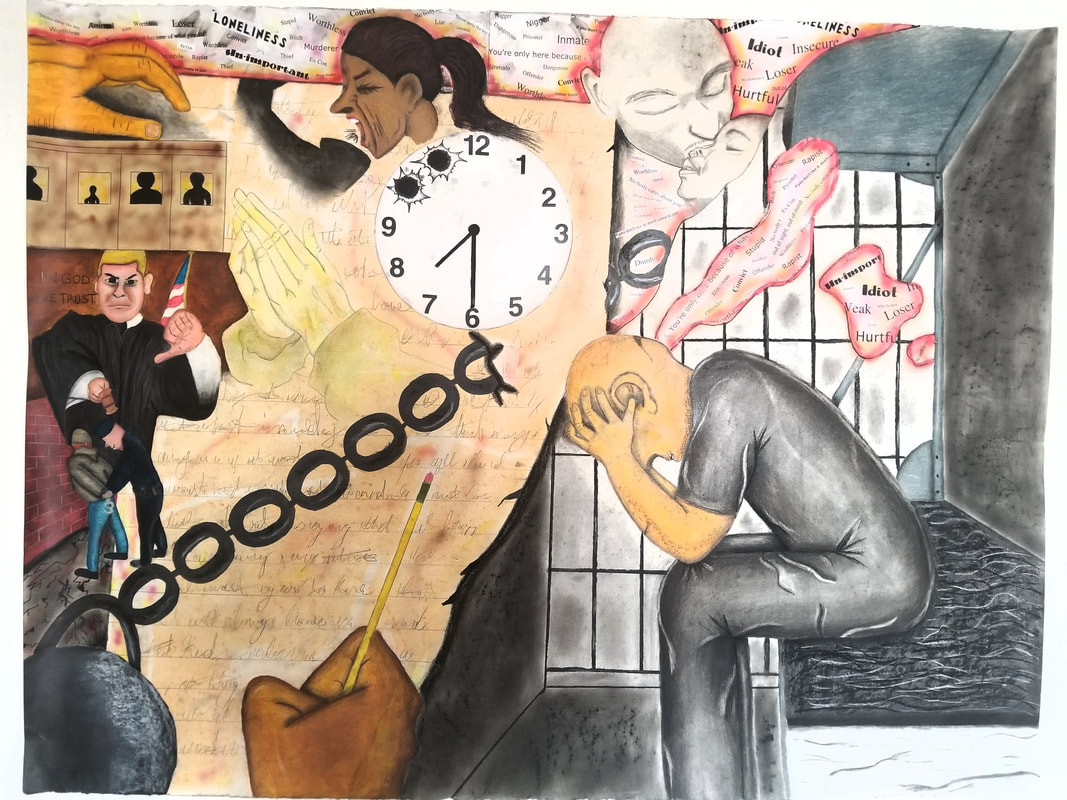

America is a violent, petty nation. The people of this country call for humane justice from the highest hills, but “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” is the way this nation handles its own failures. I’ve said much in the past about the hypocrisies of the current movement to abolish prisons. Until we clearly define exactly what true justice looks like for every group of people, we will continue to see people protest against systemic oppression in the form of incarceration for some people and justify state violence incarceration as a system of punishment. America’s go-to response, prison, is a violent monster without taste buds but with an inexhaustible appetite. The immediate emotional response when a person breaks the law is to seek out punitive responses to deter their behavior rather than invest resources and time into addressing the root causes of the issues that led to the crime. Moving toward and creating a more harm-reductive criminal legal system means that we must define accountability outside of the context of punishment. We live in a nation where the line between accountability and punishment is not clear, and because there is no distinction, the two concepts become one in their application. The most important reason that we as a nation must abandon the punishment cycle and begin to find alternatives to incarceration for every person, especially for people who are convicted of violent crimes, is because violence only begets violence, and responding to a person who becomes violent by placing them in a violent system is a recipe for disaster. Research shows that incarceration has negative psychological effects on people, including but not limited to “a dependence on institutional structure and contingencies. Hypervigilance, interpersonal distrust, and suspicion. Emotional over-control, alienation, and psychological distancing. Social withdrawal and isolation. Incorporation of exploitative norms of prison culture. Diminished sense of self-worth and personal value. And post-traumatic stress reactions to the pains of imprisonment.” Every year, hundreds of thousands of people enter the New York state prison system and while everyone is chewed up, not everyone is spit back out into society the same way, and many are left to live with the remnants of the psychological aspects of incarceration. Public safety can no longer be an excuse for this nation’s reliance on incarceration. Research shows us that prison does not keep us safe. We need to think outside of the box if we truly seek to identify nonpunitive methods for accountability, especially for people who commit heinous crimes. I admit: In my 38 years of life, I have seen and heard things that made me consider whether jail was the best place for people who commit certain acts. Likewise, as an abolitionist who is following the Derek Chauvin trial, I still struggle with the dilemma of navigating the emotional space between healthy accountability and retribution. While I want this man to be held accountable for his despicable actions, at the same time, I wouldn’t wish prison on my own worst enemy. No doubt, any time physical harm is at stake, there is a culturally responsive need for temporary separation that is time-sensitive and concerned for the well-being of all parties involved, but I do not believe that jail or prison is the separation that is needed for any form of safety prevention. Are we seeking accountability that humanizes every person involved, or are we seeking revenge against people who break certain laws? Prison should not be the answer for addressing crime or any societal issue. Prison should not be the answer to the people that society feels are irredeemable. The deprived social environment of prison can potentially impede one’s social capacity to navigate various social obligations post-incarceration, such as employment, housing, and other family and social obligations. The secondary effects of incarceration are being emotionally ignored in the heat of the moment and rather than humanizing each person by putting resources into dealing with the roots of our societal issue, the popular pejorative fosters an out of sight, out of mind attitude and casts certain people away never to be remembered again, while others are worth giving a second and third chance. Before we remain content that we can continue to send people through this violent state apparatus, we should understand that many people do not survive incarceration and that just because a person is able to avoid being rearrested, it doesn’t mean that safety is present for that individual and that the psychological effects of incarceration are not haunting them and causing equal stress in their lives and in the lives of their families. Recycling punishment is not the solution—prevention is. If we truly want public safety, then we must begin providing preventative harm-reductive solutions in four significant areas: first, mental health in order to prevent the incarceration of people who would benefit from medical support; second, social support and wellness in order to provide more therapeutic and intervention work with struggling families; third, educational support to foster knowledge, access, capacity, and opportunity amid difficult living circumstances; and fourth, economic support to address poverty and food insecurity. Until then, we will continue to be a nation reliant on incarceration. Preventing incarceration by addressing the socioeconomic issues that lead people to commit crimes is a leap toward human justice and the thoughtful abolition of our current criminal justice system. Isaac I. Scott Five-time Change Agent Award winner, Multimedia Visual Artist, Journalist, and Independent Consultant. Follow him on Twitter @IsaacsQuarterly.

0 Comments

OP-ED BY PASTOR ISAAC SCOTT IN COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR BY ISAAC SCOTT • MARCH 22, 2021 AT 11:56 PM

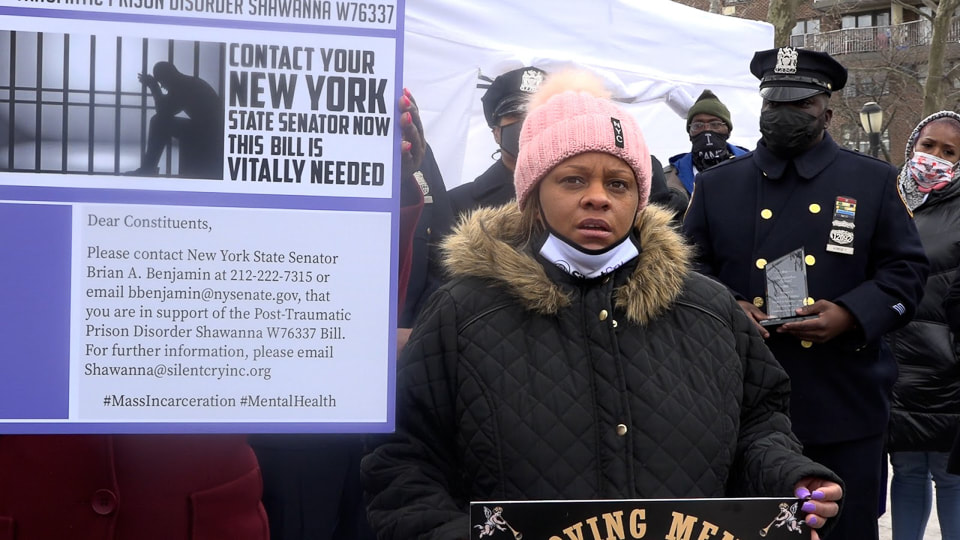

Share Too often, the role of strategic arts engagement as a transformative tool for social justice is overlooked and undervalued by leaders who don’t traditionally take artistic approaches to social change within their own work strategies. However, when it comes to creating more informed and culturally inclusive policies, the role of the arts in the social justice landscape cannot continue to be minimized to supplemental involvements, which only feature artistic activities as a secondary option for social engagement. Instead, art should be in every change agent’s toolbox as a means to change perception, build relationships, and foster action. The racial solidarity that arose from George Floyd’s murder shows us that real change will take place at the speed of the conscience of this nation and not at the speed at which we are able to procedurally change law or policy. Collective empathy can expedite justice. That said, I believe that if we want to see change in people’s hearts and minds, it is imperative for every leader and change agent to recognize that strategic arts engagement can instigate a paradigm shift in the consciousness of this country. We must begin to tap into the arts’ transformative power to create new narratives about justice, build sustainable relationships across differing perspectives, and reimagine creative solutions for problems in our community. During my time in prison, art was not only a huge way for me to psychologically cope with institutional living but also a way for me to financially provide for myself by selling my artwork on stationery supplies. Not only have I witnessed something as insignificant as an envelope with a cartoon character drawn on it serving as the first step toward restoring communication in a damaged relationship, but I have also witnessed documentary films influence politicians to take action in ways that they otherwise might not have. One recent example of the power of the arts through film can be found in Ava DuVernay’s 2019 documentary series called “When They See Us,” which depicts the false arrests and convictions of five teenagers for the aggravated assault and rape of a white woman in Central Park on April 19, 1989. The explicit portrayal of the ruses the New York Police Department and Manhattan District Attorney used to obtain confessions and convictions led to the resignation of Law School Professor Elizabeth Lederer, the lead prosecutor on the Central Park Jogger case, shortly after the film’s release. This call to action was led by the Black Law Students Associations in its call for more inclusive teaching at the Law School. Just think, under Lederer’s academic leadership, thousands of students were taught by a professor who, during the case, willfully engaged in racially biased, dehumanizing methods of prosecuting, which will potentially impact generations of Black and Indigenous people trapped in the criminal legal system. Up until the release of “When They See Us,” calls for her resignation had been unsuccessful. Later in the same year, while investigating the very unfortunate murder of Tess Majors, an 18-year-old first-year at Barnard (rest in peace), Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, enlightened by the same documentary and open to community concerns, cautioned the NYPD not to repeat the same ruses with the teenager they were questioning for Majors’ murder. Brewer’s caution ultimately led to a much more humane and restorative approach to the apprehension and prosecution of the children involved in this senseless crime. If we are to see change so swiftly through artistic methods of storytelling, I pray that every person who is seeking social change feels utterly compelled to establish the arts as a necessary, transformative tool that brings new insights and can foster relationships that will expedite the process for change to take place. As human beings with emotional responses, we are all moved by some form of the arts, whether it is creative writing, poetry, drama, music, dance, performing arts, the visual arts, the graphic arts, filmmaking, or some other art. When used efficiently, the arts can foster insight, different perspectives, and concrete actions. Many times it takes strategic arts engagement to get the point of a particular matter in a way that demonstrates the urgency with clarity. Many times it takes a drama-based warm-up exercise to bring down the guards of strangers attending a public event. This then allows for relationship-building and networking opportunities to scale the work of new and existing campaigns through strategic partnering and shared resources. Many times a visual can cause people with polar opposite backgrounds to empathize and relate across differences. Many times it takes artistic exercises to help us to imagine better methods for cultural representation and relationship-building outside of the traditional norms. And many times it takes the arts to help us to see ourselves and this nation through a social mirror for us to remove the speck from our own eyes. Pastor Isaac Scott is a three-time Change Agent Award winner, multimedia visual artist, and human rights activist studying as a Justice in Education scholar at the School of General Studies. Follow Isaac on Twitter @IsaacsQuarterly. OP-ED BY PASTOR ISAAC SCOTT IN COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR Artwork by Pastor Isaac Scott, Courtesy of Quarterly Films BY PASTOR ISAAC SCOTT • MARCH 9, 2021 AT 10:25 AM Share It is imperative that organizations and institutions actively center the voices of people affected by the criminal legal system. Moreover, organizations should not simply ask people to share their life stories or seek to offset the organization-wide imposter syndrome, but must equally center the experiential expertise and personal knowledge of those who are called upon as sources of much needed wisdom for creating inclusive environments in policy as well as under the law for Black and Indigenous people. As a father, I have done my fair share of cooking. As a Justice-in-Education Scholar who has experienced prison firsthand, I’ve done my share of creating strategies to nullify and undo the remnants of modern-day slavery found in the form of incarceration. Through my experience, I’ve found that effectively implementing a new strategy for systemic change is similar to cooking a good dish. You may have the correct ingredients, but without the proper instructions from a chef who understands the importance of each mixture and the length of its simmer, you will certainly overlook an important step or method that will cause you to prepare a meal that is far from the perfect blend. Through my own activism, I have seen many organizations try to implement the right strategies, but fail without the guidance and direction of people who have lived through incarceration. Because people just like myself with this particular lived experience are willfully confronting the justice system and seeking to expose the injustices and fallacies of the criminal legal system, it seems only fitting for us to provide some instruction on how we believe our voices, knowledge, and experience should be centered to create a better legal system. By not amplifying the voices of people who are the most knowledgeable and by structurally limiting their input, you inadvertently exploit them for the sake of your project and organizational gain. Speaking from experience, since my release from prison in 2013, I’ve been called upon to share my experience in many different capacities. Many times organizations would invite me to join their projects and speak at their public events simply for me to tell my life story for the entertaining “wow factor,” as if I was a superhuman because I survived incarceration and lived to tell about it. Many times my knowledge and wisdom was limited by the prompts and questions provided by well-intentioned, but misinformed organizers. I came to realize that I was only being involved to expose my vulnerable moments to validate or substantiate the claim of the project or initiative—not to mention that many other formerly incarcerated people are asked to tell their stories at such events without adequate compensation. Inclusion and exclusion are issues not only limited to criminal justice reform but are also very present in community-based projects. In similar ways, community input and criticism are limited and residents are excluded from the decisions that impact their neighborhoods. We can find examples of this through the lack of transparency in the New York City public arts selection process all the way to the Mind Brain Behavior Institute, which includes a rock climbing wall as a means to be inclusive to the Harlem community, but is realistically utilized only by students and researchers working within the institute. I was born and raised in Harlem, and I sure haven’t seen anyone that I recognize from the surrounding Grant or Manhattanville Houses in the facility. Real inclusiveness brings every stakeholder to the table with equal space for contribution and criticism. Whenever the voices of people are not included in the decisions that are made about them, the land and resources of the people are exploited by way of exclusion. There needs to be a paradigm shift towards targeted inclusivity for the voices of the oppressed in both legal and community office. I am speaking about diversity and representation in every sector from the New York Police Department to the District Attorney’s office all the way to organizations who service communities of color. Reimagining the justice system has to go beyond implementing new policies and strategies without clear instruction and guidance from the people with lived experiences. Activism needs to take a complete cultural shift toward inclusiveness and fair representation through employment and co-leadership, and no longer limit the contributions of formerly incarcerated people. In addition, institutions and organizations that seek to be truly inclusive cannot limit their inclusivity only to those who are directly impacted, but must also recognize those with institutional knowledge. In other words, white policy makers and community organizers must be informed by more of their Black and Indigineous counterparts who understand the complexities of their own communities. Isaac I. Scott is Five-time Change Agent Award winner, Multimedia Visual Artist, Journalist, and Independent Consultant. You perpetuate systemic oppression through your elite standards and unrealistic expectations2/16/2021 OP-ED BY PASTOR ISAAC SCOTT IN COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR Long-standing institutions that seek to move toward social correctness in 2021 are often proud to declare that those who are closest to the issue are closest to the solution and should be driving the change. While true, in its current application, this proximity to justice and advocacy rhetoric for the oppressed manifests only in mere concept. It is nothing more than rubber-stamped language rearticulated from organization to organization that expresses understanding and empathy. The reality is that well-known organizations continue to profit from prioritized funding, accessible social resources, and supportive networks that would be more beneficial to Black and Indigenous people in communities like Harlem. These benefits should be reallocated to smaller, nontraditional community-based projects and organizations that are birthed right out of the neighborhoods they serve.

OP-ED BY PASTOR ISAAC SCOTT IN COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR I believe that combatting the stigmas associated with poverty will encourage people who did not previously use state or government supplemental nutrition programs to take advantage of the food pantry and food program resources that they may need immediately.

OP-ED BY PASTOR ISAAC SCOTT IN COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR I think it’s ignorant to believe that the deeply-rooted issues in communities of color can be solved by simply taking money from law enforcement and putting it into community resources. There are greater issues regarding cultural migration, integration, and gentrification that remain unspoken in deeply impacted communities like Harlem.

While the world remains captivated by the now-famous fly that spotted Pence as the perfect matter of decay to feed on, I pose this question: Can we as Black and Indigenous families, whose lives depend upon policy change, truly expect to see legal justice, neighborhood development, and real community sustainability from either the Republican or Democratic presidential candidates?

“The Confined Arts came out of my own work as a visual artist and coming home with art and not really having a home for it,” said Scott. “Not being able to display the art, to show it, and to really exhibit my own talent. So [I decided] to make a space for myself and for other artists just like me.”

In order for you, in the fullness of your privilege, to not perpetuate subtle racism, it is important to begin gaining knowledge through actively listening to and accepting the testimonies of Black Americans without considering or offering counterarguments that would undermine the very purpose of seeking out a different point of view....

Coming Together (Digital World Premiere)Quodlibet Ensemble with Reginald Mobley, countertenor9/30/2020

Co-Presented by Baryshnikov Arts Center, Five Boroughs Music Festival, Tippet Rise Art Center + Bay Chamber Concerts and filmed by Quarterly Films, This music collaboration created for film features Quodlibet Ensemble, a collective of virtuoso string players, and countertenor Reginald Mobley, who is as passionate about baroque and gospel music as he is social and political justice. In this film, created by violinist and Quodlibet’s founder Katie Hyun in collaboration with filmmaker and human rights activist Pastor Isaac Scott, the musicians perform Frederic Rzewski's Coming Together for narrator and ensemble, with text by Samuel Melville—one of the leaders of the revolt against police brutality at Attica Prison in 1971. Weaving together footage of the musicians performing solo at remote locations, this powerful work conveys a collective journey of moving from struggle to hope amidst challenging times. The film also includes the musicians performing songs and spirituals by early 20th century composer Florence Price, and J.S. Bach’s timeless Cantata No. 54, Widerstehe doch der Sünde (Just Resist Sin), recorded September 2020 at BAC’s John Cage & Merce Cunningham Studio. The artists are partnering with VOTESart, a non-partisan organization founded by two members of Quodlibet that combines musical performances with raising awareness about voters’ rights and voter registration. SEE PRESS BELOW |

EDITOR IN CHIEFISAAC I. SCOTT, Archives

May 2024

Categories |

|

© 2020 Isaac's Quarterly LLC. The images, pictures, and videos on this website are copyrighted and may not be downloaded or reproduced. These materials may be used only for Educational Purposes. They include extracts of copyright works copied under copyright licences. You may not copy or distribute any part of this material to any other person. Where the material is provided to you in electronic format you may download or print from it for your own use, but not for redistribution. You may not download or make a further copy for any other purpose. Failure to comply with the terms of this warning may expose you to legal action for copyright infringement and/or disciplinary action by Isaac's Quarterly LLC.

|

|

|

Follow Isaac's Quarterly on Social Media

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed